You can bank on it

What does your bank account and countless unbacked units of currency have in common? The bank that holds them. Much like the government, deposit institutions don't have backing for everything you deposit. In fact, they only hold a fraction of paper money and coins for the deposits they have on account - which, if you recall, is only backed by a tiny fraction of actual metal.And here's where the technology comes in - though the banks only house a fraction of the demand-deposit (checking and savings) currency, you are legally entitled to have access to 100% of it - and if it's a decent bank, you should be able to do it from anywhere in the world. So, your account gets stored digitally to be accessed from over the wondrous interweb (and all of its tubes, thank you Sen. Stevens) by ATMs and banks worldwide.

This brings us to our first technologies - Debit and credit cards.

Plastic Money

We are all familiar with the basics of debit and credit cards, so I won't bother with the most basic mechanics. What I will bother with is the technology - thanks to the handy 12 to 16 digit number, point-of-sale transactions have never been easier. But how does it work?Well, after you buy something with a debit or credit card, your card's data (which was hopefully swiped via PDQ) is passed to a payment gateway via SSL. Once the payment gateway gets the data, its software verifies all of the credit card information and accepts (or declines) your card. If this is an online sale, the payment gateway will automatically send an email receipt to both the merchant web server and to you.

After that, the payment gateway sends the order to the merchant bank to initiate a fund withdrawal. The full amount of the transaction then gets subtracted from your account, and most of that gets placed in a 30-day holding account owned by the merchant. The small difference between withdrawal and deposit (usually 1-2%) is kept as a fee by the payment gateway company and card network (Visa, Mastercard, etc). This fee is known as a discount rate.

The 30 day holding period is meant to help prevent fraud - if there is a problem on either end of the sale, the money can be frozen until the dispute resolves. Credit and debit fraud is more common than many would think, sadly. To combat this, card companies (who eat the buck for most of this stuff) have had to play with some risk-based price models. The more a business deals with Customer-not-present (telephone orders or internet orders) sales, the more that the discount rate is.

The 30 day holding period is meant to help prevent fraud - if there is a problem on either end of the sale, the money can be frozen until the dispute resolves. Credit and debit fraud is more common than many would think, sadly. To combat this, card companies (who eat the buck for most of this stuff) have had to play with some risk-based price models. The more a business deals with Customer-not-present (telephone orders or internet orders) sales, the more that the discount rate is.Statistically, it's twelve times more likely that a credit card transaction is fraudulent over the 'net than it is over any other medium. Therefore, many internet payment gateways have started taking on extra precautions to lower fees. These range from the use of post codes to entire address verification, and usually accompany the verification of the CVV2 code on the card itself. This little three-digit number is not printed or transmitted anywhere except a tiny spot on the signature panel of the card, so only someone with the physical card present can make a purchase.

Since signatures are so easy to forge, Europe has gone one better on fraud prevention even at point-of-sale locations - PINs. Rather than signing for a transaction, all you have to do is input your four-digit super-secret-oh-my-god-don't-tell-anyone personal identification number into the keypad and off you go. This digital seal is a whole lot faster than signatures, and comes with another bonus - it is incredibly secure.

The US uses PIN numbers as well, but only for debit cards and often this incurs a fee from the consumer's bank. Instead, we still rely largely on signature verification here - despite the fact that cross-eyed Sally across the counter from you couldn't even read the words "SEE ID" you wrote in black magic marker across the back of your card.

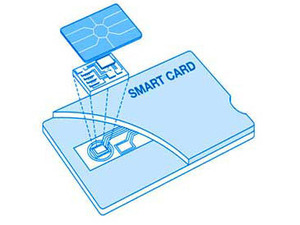

It's smarter than you are, as soon as we figure out what it does

Nowadays, lots of plastic comes with a fun little spot of gold close to the left hand edge dubbed a Smart Card. No, it's not just there for looks - but it's a technology that's just really starting to take off now, despite going into mass use as far back as 1983.Smart cards don't just hold your info on that chip - the card actually houses a microprocessor capable of manipulating the encrypted data directly on the card. The gold contacts visible on the surface allow a reader to access the information, which is usually a bunch of security info. Though the card still requires a PIN number to use for larger transactions, small ones can now easily be accepted with just a wave of the card over a scanner.

The entire Smart Card benefit has been largely lost on the US, which is just bringing the technology into use now. McDonalds and other fast food locations have recently put Smart Card scanners by their drive-through ordering windows, which prevents clerks from ever needing to see the card while imposing the least hassle on drivers in line. Who said fast food gives you nothing but heartburn?

All this is great, but we can get even better than plastic. How about...

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.